DISASTER AT BAYLEY BAY -- 1966

Explorer Scouts Rescued Six from Death by Hypothermia

Walter Trapp, then aged 32, a science teacher at the High School in Gibbon, Sibley County, Minnesota, had been a guide in the Boundary Waters area and the Quetico for several summers and conceived the idea of guiding three or four of his high school students on a canoe trip to acquaint them with the good life, as he had experienced and told of it. Perhaps he wanted to justify some of the tales he had told. Why not? Walt had been a muleskinner in the U.S. Army, a vernacular term for a soldier trained to pack and drive mules. He was a mulepacker in Battery A of the 4th Field Artillery Battalion (Pack) at Fort Carlson, Colorado. The battery was armed with the 75mmm Pack Howitzer M1-A, which required 6 mules to pack it and another 6 to pack ammunition for it, and was used in mountain and jungle terrain and for air dropping, because it was designed to be disassembled. Mountain troops were supplied by strings of mules packing various cargos, and Walt's unit was the last of its kind in the U.S. Army, inactivated on 15 December 1956.

Walt found no difficulty in adapting his mountain experience to the lakes of northern Minnesota. He understood that it would be politic to have another adult along on a trip with boys and found me a willing partner. I was aged 31, from Claremont, New Hampshire, and had been a teacher of English at Gibbon High School for one year, having taught previously in Newbury, Vermont. Son of an innkeeper who had been a hunting and fishing guide in Maine and New Brunswick, I had many years of outdoor experience in the United States, Canada, and the Yucatan in Mexico. I had also served in the 45th Division during the last campaign of the Korean War and for a year in that country thereafter, living in a tent for well over a year, including the cold winter of 1953-54. But, seeing is believing, and being a prudent man, Walt proposed an overnight cruise down the Minnesota River, no doubt to see if I could paddle. Yup. I learned in my father's classic 18-foot Chestnut on the Connecticut River as a child and had been a paddler in my Granduncle Michel's big freighter on Lake Champlain; 20 to 22 feet long that canoe was, and about four feet wide amidships.

--Paul Gaboriault and Walter Trapp, 2007

Using several Fischer maps of the Boundary Waters and Quetico Provincial Park that he had acquired, Walt thought we could get as far north as Kawnipi Lake and return within a week and have time to do a little fishing along the way. He was accustomed to using motors to go further than he could by paddling; this time the intention was to go to a specific lake and back within a limited time. The plan was to expend a little less than half our gasoline, then cache the motors and gasoline cans and paddle as far as time permitted, then circle back to the cache to get the motors and gasoline for the return.

On 06 June 1966 we set off from Gibbon, Minnesota, and began the 300-mile drive to Ely. In the morning at about 10:00 a.m. we stopped at Ely High School just "for luck" to see if there were any openings for teaching English: there was one, for someone qualified and willing to teach five classes of 12th grade English, and I was hired on the spot at significantly more than I was paid in Gibbon--subject to my credentials being what I said they were. No problem. Moreover, there was plenty of time for me to resign honorably at Gibbon, for there would nearly all summer for the Superintendent of Schools there to advertise for an English teacher and interview candidates

We got to the public landing on Moose Lake and arranged with an outfitter nearby to leave our vehicles in his care for a week, paying a reasonable fee for the privilege. While we were assembling our gear for putting in and loading, Walt noticed a man having some difficulty with tying down a tarp over a trailer. He went over to help and within a few minutes had tied a magnificent diamond hitch that lashed that tarp down in style. I determined then that I would learn to tie a diamond hitch, and eventually, I did. The chief value of such a hitch is that no matter how uneven the shape of the cargo or how difficult the terrain, and whether one carries cargo in a truck or trailer or by pack animal, the diamond always adjusts as the cargo shifts its weight, so the hitch keeps the cargo secure. It is a good way to lash a pack and stuff sacks to a packboard.

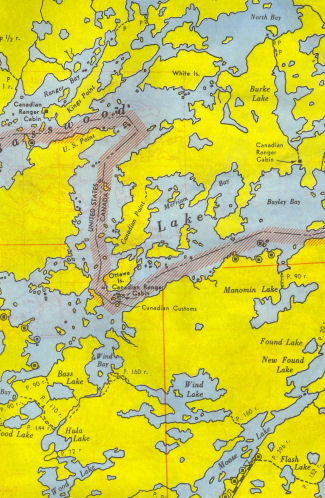

We left Moose Lake Landing, the usual entry into the Boundary Waters wilderness, about 2:00 p.m., traveling in two square-stern Grumman canoes (3), powered by 5-h.p. Johnson outboards, both companies so reliable that their various products had become among the standards for outfitters (2). In each canoe was a five-gallon can of gasoline. It was an overcast day, cool with intermittent rain. We proceeded up Moose Lake to the 10-yard portage to New Found Lake and then into the contiguous Sucker Lake, thence to Prairie Portage, which was about a 40-rod carry from Sucker Lake into Inlet Bay of Basswood Lake. Along the portage, we stopped at the Canadian Ranger Station to get permits to visit the Quetico. It was a grey and overcast day, and by 3:45 p.m. we were proceeding along the eastern edge of Inlet Bay into Bayley Bay, which was also a part of the huge many-armed Basswood Lake, steering a course toward Portage Point, at the northern end of the Bay, and to North Portage to the east of that point. Just as we got past Shelter Island to our west, probably so-called because it shelters the strait between Inlet Bay and Bayley Bay from the prevailing NNW winds, we were in the teeth of a north wind, 15 to 20 m.p.h., gusting to 25 m.p.h. or more, and there was a considerable swell on the big expanse of water with long rollers coming down the lake and spray wetting us.

We started taking on water. I was in the bow of our canoe, with Clifford Anderson at the tiller and Les Pettis at the middle thwart. Cliff was a recent high school graduate from St. Paul, Minnesota, the brother of Ted Anderson, a teacher and coach in Gibbon. I tried to keep the spray from entering at the bow as we pounded our way through the swells and whitecaps, using my poncho as a shield; and Les bailed as well as he could; but a few hundred yards past Shelter Island, steering a course more westerly into open water than we wanted, we swamped and rolled over. Cliff had the good sense to kill the motor as we swamped. Walt was at the tiller of his canoe, with Gordon Anderson at the waist and Steve Lewis at the bow. He was cruising about parallel with us and saw our trouble as it happened. He immediately steered in a big arc through the swells, avoiding broaching by both skill and luck, and managed to get just about to us, but by then his canoe had shipped enough water to swamp. Then we were all in the water. Six of us. I don't know how Walt thought he would rescue us, but he surely was going to try. He didn't get the opportunity.

Disaster at Bayley Bay!!!

At the very start of our voyage. What an ignominious fate! My focus got very restricted after that. Being low in the water, I couldn't see Walt's canoe or its occupants. The water was cold, perhaps 45 F. or less, even in June, but I hardly noticed the cold; I was too busy.. At first I felt only chagrin, thinking that, surely, I'll be remembered as a trou de cul, not an outdoorsman. I was vexed nearly to tears by my sense of humiliation and shame. Then, I thought of the boys and the obligation Walt and I had to get them home safely. Horrified at my helplessness to go to their aid, I finally realized that I was hanging onto the canoe by the gunwale, I think on its port side near the bow, and that I was being battered on the head by the canoe, which had righted itself because of its flotation chambers and loss of most of its cargo. I was enveloped in a poncho, which hampered me. Our gear was floating around. I saw my No. 4 Duluth pack starting to sink, and I grabbed it with my right hand, having my left hand on the gunwale. In a few moments I let it go and it sank. There was a Zeiss Ikon 120mm camera in there, and an Eagle Claw pack rod in a screw-end aluminum case, together with a brand new Abu 3000 bait casting reel, and it mattered a lot, but just for a few moments. Then I saw that my hand on the gunwale was bleeding and I noticed some canoes very near us. My despair changed to hope, but not for long, as first one than another, perhaps six or eight canoes went by us without their paddlers giving us more than a quick glance, if that.

They were headed toward shore somewhere and did not stop. I saw someone's musette bag start to sink and could not save it. I thought of the folkloric Mishegenabig, the great horned water serpent of the Algonquians, which dragged down canoes, cargo and paddlers to the depths where it lived, and of Animiki-binesi, the Thunderbird, its nemesis, which soared down from the heavens with clutching talons if the serpent dared to surface: we should have propitiated the former and supplicated the latter but had done neither (5).

I was getting enormously tired from trying to hang on to the canoe and from the battering and the cold water. My boots seemed to be dragging me down. Despite my life jacket, I seemed to be very low in the water and breathed in a little of it from time to time, which I managed to cough out. But then a canoe came upon us. A paddler asked if I was all right. I responded that I had a cut hand; my focus had become so restricted that a little blood was my chief concern. I saw neither Clifford nor Les in the water. I didn't learn--or I couldn't remember during an intervening 40 years--what happened to Walt and to Gordon and Steve with him nor how they were rescued. There was another paddler with the first, and I believe they got Les into their canoe. What happened to Clifford I can't recall. Perhaps I never knew. I think they got a bowline around my chest just under the arms and hauled me though the water as they struggled toward the shore. I recollect holding onto the gunwale of their canoe at least part of the time. I was on their port side. After a while that seemed a long time we landed on what proved to be the north shore of Shelter Island. By then I was feeling warm but my hands and feet were numb. I experienced a lassitude that was not unpleasant. On the island I fumbled with my rubber boots, which had filled with water, but could not make my fingers untie the four wet laces at the top. The boots fit tightly at the ankles and I could not budge them. Someone helped me get them off. I never put them on again. I shucked off my poncho and discarded it. After our rescuers had rested, we set off, circling around the island to its east and thence to the mainland, Les and I kneeling on the bottom of the canoe in the middle. I felt the wind and spray as we headed into it, but no cold, though I was soaking wet. All I can remember was a long, heaving, wallowing glide to land.

Eventually we came to shore at a cove about due east of the island, where a troop of Girl Scouts from Ely were encamped, windbound on their way home from a long voyage. I was helped to get ashore and greeted by a number of young women who had taken charge of all of us. I remember fumbling to remove my clothes and crawling into a sleeping bag and nothing more. The bag must have been underneath a fly of some kind, but it was not in a tent. I was told later that I was given soup and cocoa and that warm stones wrapped in cloth were placed in the sleeping bag. I must have solicited the names of our rescuers, for I had a scrap of paper with the names of three of them written on it. Maybe someone else wrote down their names, but I had the piece of paper with me in the sleeping bag. There may have been more than three rescuers. But I can recall nothing after I got into the sleeping bag. I suppose I had to get up during the night but don't remember doing so.

Upon awakening, I discovered a pleasant morning and saw my clothes neatly folded beside me. Underwear, sox and outer clothing had all been toasted next to an open fire and were bone dry with a woodsmoke smell. My Herter's twill "Alaskan Tuxedo" trousers had changed in color from a dark olive to a brown-olive from the toasting and smoke, as I saw later when storing them with another pair. Both pairs lasted me for many years but were never the same color again. My hand had been bandaged with a few wrappings of bandage, the end split and neatly tied , and young ladies in the vicinity discretely turned their backs while I dressed. I had some porridge for breakfast. I learned that Walt, whom I divined had not been in the water so long, had maintained sufficient strength to assist the Explorer Scouts who rescued us in the retrieval of our canoes and motors and such of our gear that had floated. Once everything was on shore, Walt, as were the others, was bundled into a sleeping bag. Forty-one years later at a high school reunion in Gibbon, Minnesota, I learned that Walt had clung to a gasoline can until he was rescued, and that though he was in the water quite some time, he did not feel cold. From Les Pettis at that reunion I learned that he and Gordon Anderson had also been dragged or somehow conveyed to the same island as I--the only one in the vicinity--and that may have been before I was there, for I do not remember seeing either of them on the island.

By mid-morning of 11 June 1966 we were on our way again, somewhat lighter now with more freeboard, having lost some major equipment and provisions. Very little of my gear had survived, but I did have my down-filled Model 1949 U.S. Army Mountain bag, the kind that was issued to us in Korea. I bought it as surplus with a water-repellant cover for $35.00. It had been packed in a waterproof stuffsack with a plastic ground cloth and had floated. By great good fortune, rolled up in it were a pair of lightweight hang-around-the-fort moccasins and a knitted wool tuke, both of which I habitually used around a camp fire and during the night. It was an overly warm bag for summer use, but I had no other and opened the zipper all the way. North Portage to Sunday Lake is a 120 rodder, then one travels NE the length of Sunday to a due-east 160-rod portage called "the bitch" that ends at the northern tip of Meadow Lake. A very short paddle around a 90-degree angle to almost due north leads to a 140-rod northeasterly portage called "the bastard" that goes to Agnes Lake. Maybe the names of those portages are the other way around. Perhaps the names are not official: many portages in the canoe country have those names and some have others even less complimentary. Once on Agnes, we found a campsite at a rocky little point on the eastern shore, not far past the beautiful Louisa Falls, which descends some 90 feet or more in an interrupted cascade. Agnes Lake is at the beginning of the beyond, and we were the only interlopers on its solitude. It is some 2 ½ miles long and a mile wide, bound by rocky cliffs with evidence of occasional rock slides. It has restless winds. I was sufficiently charmed and restored to borrow Walt's fishing rod and catch an excellent Northern pike of 7 lbs. or more, which I dressed on a canoe paddle and Walt cross-cut --"steaked"--for the frying pan. Walleyes that others had caught were filleted, and we enjoyed a primitive feast--primitive, because we had little else but fish and some raisins. I do remember that we had salt. I was so heedless of propriety as to say to Walt within hearing of the boys that after our misfortune I never expected to spend a night on Agnes, and they were alert enough to respond to the double-entendre with a gale of laughter, an incident Les Pettis related to me 40 years later. Walt took the boys off a ways to see some pictographs on rocks along the lake, but I lolled around the fire, wearing my zipped-open sleeping bag draped over my shoulders like a blanket in the cool of the evening. Indeed, for all of us the magic was gone. We had survived a canoe voyage to Hypothermia, but after such a life-threatening adventure everything was anticlimactic. So, on 08 June we left our campsite early and arrived back at Moose Lake Landing in the afternoon.

Who the Rescuers Were

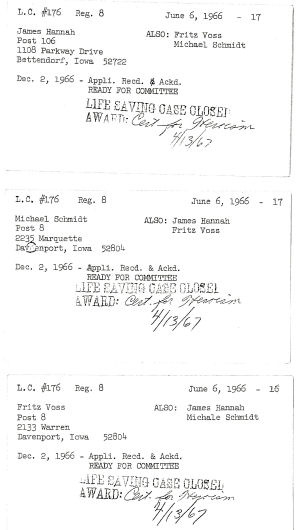

Returning to Gibbon, Minnesota, we told our story to our friends and relatives. The boys were gleeful with their adventure, though it had not been the one intended. I made a few enquiries and wrote to the now defunct Buffalo Bill Council, Boy Scouts of America, in Davenport, Iowa, about the rescue, and recommended that the three Explorer Scouts, Robert Hannah, Michael Schmidt, and Fritz Voss, receive a lifesaving award, stating that, in my opinion, they had saved six of us from death by hypothermia at considerable risk to themselves. I included my thought that there may have been other Explorer Scouts who participated in the rescue and my hope that, if so, their names would be revealed and that they would share in the award. Then I drove to New Hampshire, traveling across the Upper Peninsula of Michigan to Escanaba and via Canada Route 1 to Rouse's Point, New York, and thence to South Hero, Vermont, and down the state to my parents' home at Ascutney, Vermont. Shortly after my return to Ely in late August, I received a letter from the Buffalo Bill Council, forwarded from Gibbon, that the three Explorer Scouts had received an award with an enclosed newspaper article to that effect. There the matter rested for 41 years.

Thereafter, I served as an adult leader from time to time in a Boy Scout troop in Franklin, N.H., and in Superior, Wisconsin. I was highly gratified that my son earned the Eagle Scout rank in Superior. In 2005 I became the Troop Committee Chairman of a newly founded troop in Rhinelander, Wisconsin. In 2006 I sought Wood Badge training and received it at Camp Stearns, B.S.A., near Fairhaven, Minnesota. Because of the tragedy in November, 2006, when James Kim died of exposure and hypothermia in Oregon, I thought that one of my Wood Badge tickets might be to establish a website pertaining to Scouts and hypothermia, including planning to prevent it and treatment for it. Anecdotal accounts would be central to make the site interesting and a celebration of Scout training and its far-reaching benefits would be featured.

As a consequence, on 16 January 2007, I wrote to the Boy Scouts of America in Davenport, Iowa, and received a reply from Mr. Thomas P. McDermott, Scout Executive of the Illowa Council, successor to the Buffalo Bill Council. I also wrote Mr. Roy Booker, Librarian of the Quad-City Times, to see if a newspaper article could be found, since I know that one was published, having received a clipping in 1966 or 1967. He looked, and communicated by email with Mr. McDermott, but had no luck. Both wrote me cordial replies and we exchanged email messages during about a month. Eventually, Mr. Jim Rogers, Program Director of the Illowa Council, after spending time on several false leads, contacted Ms. Christel Jackson, of the National Office, B.S.A. She had a cardex file, designated "National Court of Honor S209," which contained a card for each of the three Explorer Scouts. In addition to sending Xerox copies of the three file cards, she sent the following message: " At that time there was no medal--just a certificate. However, if they are still involved in Scouting, they could get a Heroism Uniform Knot for $3.50 each." According to the Internet, the Scouts would be eligible retroactively to receive the medal that replaced the certificate. If the Scouts can be located--they would be in their middle 50s now--I should be delighted to travel anywhere to participate in such an award. In my thanks to Mr. McDermott and Mr.Rogers, I stated my willingness to participate in an awards ceremony could they locate the Scouts.

Of the Girl Scout Troop from Ely, the late Mary Catherine Brown was Troop Leader in the summer of 1966, and her Assistant Troop Leader was Marian R. Cherne (1). I spoke by telephone with Marian Cherne in June, 2007, who was then in Ely, Minnesota, and who remembered the incident at Bayley Bay. Unfortunately, she did not have a record of the individual Girl Scouts. At one time I compiled one, having a few of the older Girl Scouts of the Troop in my classes, but the list has disappeared. I am trying to locate someone who knows the Scouts and their Troop number. Of course, Mary Catherine Brown had a record of her Troop, but she died in February, 2005. She founded the St. Mary's Episcopal Church--Ely, in the 1970s. She was a lifelong Girl Scout and former owner of the Paul Bunyan store in what is now the Boundary Waters canoe area. She willed the Mary Brown Environmental Center to the Episcopal Diocese of Minnesota. I met her several times during my employment as a teacher of English at Ely High School during the academic years 1966-67 and 1967-68. The first time I met her, she stated, "I was in charge of the Girl Scouts who helped to rescue you at Bayley Bay." I can remember responding, approximately, "Madam, I hope I never give you cause to regret it." I wonder if a certain incident was ever reported to her: I had about 125 students in my five English classes, but nevertheless, I required a writing assignment nearly every week, which caused me almost killing toil; but no one ever called me lazy. Among the first assignments in the fall of 1966 was a theme describing the most interesting thing that had been seen during the summer. One young woman--my students were all 12th graders--wrote that the most interesting thing she saw was the bare arse of the English teacher.

Where We Went Wrong

Through the years I have learned that a lot of canoes swamp on Bayley Bay, which has a deserved reputation of being a wind corridor down its three mile length from the north. Most people are able to get ashore somehow, but some have to be rescued. I have not learned the number of fatalities during the last 50 years, which would be enlightening. We had no plan for coping with an upset. The swimming ability of each member of the group was unknown or, at least, was not known to all. Elementary survival gear, such as a jackknife secured to the belt by a lanyard and a supply of matches in a waterproof case was not carried by everyone. Today, a hip-pocket survival bag weighing just a few ounces might be a good item of gear to have. The knowledge and ability of each person to start a fire was unknown. Footwear appropriate for canoeing was not worn by everyone: I was wearing rubber boots somewhat like Wellies but tighter around the ankles and hard to remove and was wearing a poncho, which is not a garment to swim in. Such boots might be good on a gumbo portage but are good for little else. I never wore a poncho again. We were a little far from shore, but we had gotten that way by the need to steer into the wind and swells. We had too much gear. Our most valuable items could have been lashed to the canoe. We all had PFDs, but mine was not adequate for my weight, 215 pounds then. All of our duffel should have been packed so that it would float.

But principally, both Walt and I had taken chances on many treks and voyages and had always managed to get back. We had grown complaisant. We had to learn the hard way that "Good judgment comes from experience, and experience comes from bad judgment."

The Motor Controversy

Generally speaking, the use of outboard motors with canoes is justified for ascending rivers against the current, for trolling for fish, and for covering a lot of distance in a limited time. On the negative side is the noise, the contamination of pure water with traces of gasoline and oil and with exhaust gases. In addition, motors tend to give the user a false sense of security, since headway is made at a constant speed, though it is not fast with motors suitable for canoes. And, a can of gasoline is one more piece of heavy cargo. Finally, if the motor is disabled, there is the dead weight of the motor and its gasoline as part of the cargo to be paddled. I suspect that one reason Walt decided to use motors on our voyage in 1966 is that the boys had had limited experience with canoes, and he thought it would be an easier voyage if they didn't have to learn paddling while we were traveling. But they would certainly learn if one of the motors was disabled.

The Signs of Immersion Hypothermia

According to Dr. Alan M. Steinman, "Using 25 C. [Celsius or Centigrade = 77 Fahrenheit] as the definition of cold water, the risk of immersion hypothermia in North America is nearly universal most of the year (Steinman 2007)." Water temperatures in New Found Lake, New Hampshire, average about 62 Fahrenheit in June, according to officials of the Moosemen Triathlon (1.2 mile swim, 56 mile bicycling, 13 mile run), who strongly advise a wet suit for the swim. The average water temperature of Basswood Lake, Minnesota, averages from the high 40s Fahrenheit to the middle 50s Fahrenheit in June.

It is startling to learn that immersion hypothermia leads to drowning (Steinman 2007). With an average body temperature of 98.6 Fahrenheit (37 Celsius), a person is in water that is approximate neutral at 91.4 - 95 Fahrenheit (33-35 Celsius), that is, heat loss and heat production are approximately the same. In water below this temperature, hypothermia results eventually, and in water colder than 77 Fahrenheit (25 Celsuis) the incipient dangers of hypothermia result. These steps are outlines and explained by Dr. Steinman in his various articles and books. Strange to the layman is that drowning can be the result of hypothermia, due to a gasp response initiated by rapid skin cooling and, in heavy seas, the subsequent inability to hold one's breath.

It may be possible to contract immersion hypothermia without actually being immersed if one is subjected to a protracted cold rain and wind. About the year1980 Robert Henderson, a graphic artist from Superior, Wisconsin, went on a bicycle trek from Duluth, Minnesota, all around the northern border of Lake Superior, stopping now and then to sketch scenes for painting later. He was caught in a cold driving rain that lasted many hours. He is convinced that had he not had an aluminized plastic survival bag to crawl into, he would have died from exposure--from immersion hypothermia.

Why Didn't Other Canoeists Help Us?

Studies have been undertaken as attempts to learn why bystanders or witnesses to attacks of various kinds, robberies, accidents, fires, floods and other natural disasters are content to do nothing or literally flee from taking part in rescue efforts or assistance to victims. One phrase applied to the phenomenon is "bystander apathy." Some people are more critical than others of what is appropriate to do for others; they are not at all altruistic: "They got themselves into it; let them get themselves out." Some people are more calculating than others, making a careful assessment of the possibilities of success versus failure, the liabilities, dangers and risk. But, probably, the reason so many bystanders do nothing is that they are fearful and feel helpless themselves. They have never been trained to do very much. They don't know how.

Boy Scout Training

Boy Scout training is fundamental to accomplished canoeing and boating. One can move on from that level to more technical and higher levels of skill, but Boy Scout training for beginners is as good as it gets. A concentration on teamwork and all it implies follows individual instruction, and the "buddy system" works for adults as well as youth. There are a few techniques that are taught in Scouting that are not universally applicable, such as hauling a swamped canoe crosswise over another to rock out water and right it--which works well on a placid millpond where an upset or swamping is not likely to occur, but which is next to impossible to perform in a heavy sea on big water where an upset or swamping almost certainly will. But the concept behind such a maneuver, the teamwork, the intention to help somebody else--the people in the other canoe--is all good training and preparation, perhaps the inculcation of altruism, or, at least, the channeling of it.

In our swamping in Bayley Bay in 1966 the Explorer Scouts knew how to help us, and they did. They did, because they knew how. Of course, training must be accompanied with daring and expertise. And they had plenty of both.

Be Prepared

To be prepared for a safe canoe voyage means that one must first be in good physical condition. Good mental training helps. It is wise to have a plan concerning what to do if your canoe swamps or upsets. Walter Trapp exemplified how one man should judge another as a potential partner by taking me on a shakedown cruise. He learned something, all right, but he had to learn a lot more the hard way. One should know the basics of survival; there are plenty of books about it available. All good athletes know that there is such an attribute as psychological preparedness, which is a combination of self-knowledge, physical conditioning and positive attitude. Psychological preparedness may mean the difference between active maneuvers to right a swamped craft by rocking water from it, entering it and bailing out the rest of the water; or holding on to a swamped craft and assisting the wind to get it to shore or shallow water; or swimming to shore if the wind is blowing the wrong way or the water is too cold to stay in it more than half an hour--as contrasted to passive waiting for rescue which may come too late or never. Teamwork likely will be necessary to right a swamped craft, and teamwork by definition requires someone in charge, every member knowing his part to perform, and practice, practice, practice.

A little-known fact is that it is possible to build up a tolerance to cold-water swimming. Studies have shown that people can acclimate themselves to swim in cold water, beginning with a wet suit and eventually swimming without its protection. Basic to canoeing preparedness is learning about PFDs (Personal Flotation Devices) and being sure you are wearing one that is adequate for your weight and body type. One should practice swimming in one--practice a lot. Fundamentally, one must be alert--know what he is up against at the time of the year he is voyaging, and be ready to leave the canoe or other craft behind under certain conditions: According to Dr. Alan M. Steinman, "If you stay with the boat too long in cold water, you're going to drown anyway. If there's no likelihood of a quick rescue, and the shore is reasonably close, a strong swimmer may be better off swimming for it (Steinman 2003, 79)." It behooves every outdoorsman to know what immersion hypothermia is, its signs, stages, dangers and how to prevent it and treat it.Responses to this Website

This website is a work in progress. It will be corrected and improved as responses make that possible. Anecdotes and accounts of Boy Scout experiences in cold water, both of their survival of mishaps and of their attempts to rescue others, and awards they have received for rescues, are particularly wanted.

Responses to this website are solicited. Kindly contact: Paul H. S. Gaboriault using the contact form.

NOTES

(1) Thanks are expressed to Rebecca L. Rom, J.D. (Mrs. Reid Carron), for assistance in contacting Mrs. Mercedes Thompson Leustek, of Ely, who, on my behalf, is investigating the names of the Ely Girl Scouts who participated in the rescue on 06 June 1966 and the identification number of their troop. It was Mrs. Leustek who contacted Marian R. Cherne and sent me her telephone number. Rebecca Rom is the daughter of pioneer outdoorsman and Boundary Waters Canoe Area advocate Bill Rom, who was proprietor of Canoe Country Outfitters in Ely, Minnesota, up to the 1970s. Rebecca was an expert canoe guide as a teenager.

(2) Grumman's boat division was sold in 1990 to Outboard Marine Corp. In July, 1996, OMC produced its last Grumman canoe. But a few months later four former Grumman and OMC employees and an investor formed Marathon Boat Group, Inc., and began manufacturing again at the old Grumman plant at Marathon, New York. Though canoes made of Kevlar and other synthetic, plastic and composite materials have made significant inroads on aluminum canoes as a standard for outfitters and canoe liveries, the strength and durability of Grumman canoes continue to make them a popular choice for outdoorsmen and explorers.

(3) Grumman's sixteen-foot square-stern canoes were actually 15' 7" with a beam of 36 1/4" and had a capacity of 655 lbs., cargo and personnel. In 1966 I weighed 215 pounds at nearly six feet one, so with two others and our duffel plus an outboard motor and a five-gallon can of gasoline, we were "crowding" the capacity a little.

(4) An excellent article on the "numerous ideological and political battles" concerning the Boundary Waters is Michael Furtman's "75 Years of Canoe Country Advocacy," in Boundary Waters Journal , Vol. __ , No. __ (Autumn, 1997): ___ - ___ .

(5) "... I have seen that in any great undertaking it is not enough for a man to depend simply upon himself. --Lone Man [Isna Ia-wica] (late 19th century), Teton Sioux (Aaron 1994, 51). Nor even in small undertakings--Paul H. S. Gaboriault.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Aaron, Gregory C. and David Borgenicht. Native American Wisdom. Photographs by Edward S. Curtis. Text researched by Gregory C. Aaron and edited by David Borgenicht. Pictures researched by Elizabeth Broadrup. Running Press Miniature Edition. Philadelphia: Running Press Book Publishers, c. 1994. 128 pp. 2 3/4 X 3 1/4 inches.

______ ______ ________ . "Bayley Bay Rescue" in Boundary Waters Journal, Vol. 15, No. 2 (Fall, 2001): ___ - ___ . (What went wrong on their voyage?)

Edwards, Bill. "Swimming with Polar Penguins." USMS SWIMMER, November-December 2007: 19-23.

(Founded in 1970 as an organization of sportsmen and sportswomen, United States Masters Swimming is the governing body for adult swimmers in the United States, dedicated to the premise that the lives of participants will be enhanced through aquatic physical conditioning.)

Steinman, RADM Alan M., M.D. "The Facts About Falling Into Cold Water." Editorial in The Standard Times, Bedford, MA, 14 February 2005.

Steinman, RADM Alan M., M.D. Immersion Hypothermia, Near-Drowning and Water Survival. In: The Ship's Medical Chest and Medical Aid at Sea. 2003 edition. Public Health Service, Office of the Surgeon General. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

Steinman, RADM Alan M., M.D., and Gordon G. Giesbrecht. Cold Water Immersion. In: Wilderness Medicine. 4th edition. P. Auerbach, editor. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby, 2001.

Steinman, RADM Alan M., M.D. "Immersion Into Cold Water." Abridged from Cold Water Immersion. In: Wilderness Medicine, by Alan M. Steinman, M.D., and Gordon G. Giesbrecht. 4th edition, P. Auerbach, editor. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby, 2001. Internet article, accessed 21 December 2007 in Experts.com-The Premiere Expert Witness Directory: <experts.com/show Article.dsp?id=20>

Triathlon Races - Moosemen in New Hampshire. <www.timbermantri.com/moosemaninternational.html>

GRAPHICS

Bayley Bay, Basswood Lake (detail), from "Superior-Quetico Canoe Maps, No. 112: Burntside-Basswood Lakes." Virginia, Minn.: W.A. Fisher Co., c. 1952. Printed on vegetable parchment, 21 1/8 X 16 5/8 inches (image) with 3/8-inch borders.

Bayley Bay, Basswood Lake (detail), from "Superior-Quetico Wilderness Canoe Area" map. Virginia, Minn.: W.A. Fisher Company, c. 1964. Printed on vegetable parchment, 21 X 32 1/2 inches (image) with 5/8-inch borders.

Bayley Bay, Basswood Lake (enlarged detail), from "Superior-Quetico Wilderness Canoe Area" map. As supra.

Cards, Cardex File, National Court of Honor S209 (copies). National Council, Boy Scouts of America, Inc., P.O. Box 152079, Irving, TX, 75015-2079. c/o Ms. Christel Jackson (2007).

Photograph, Paul Gaboriault and Walter Trapp, ages 72 and 73. Gibbon High School Reunion, Gibbon, Sibley County, Minnesota. __ August 2007. Photo by Marian E. Gaboriault.